Date: June 30, 2019

Abstract

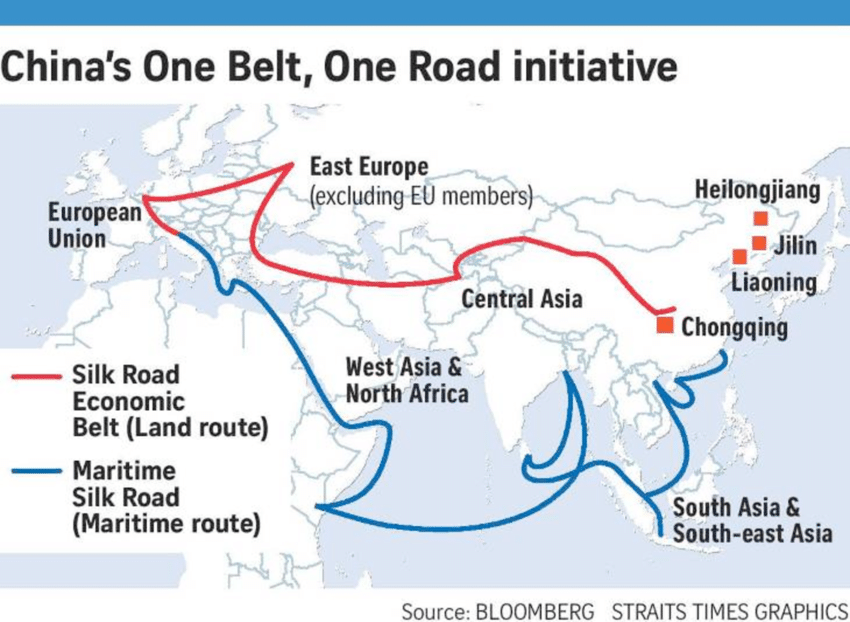

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was created by China in 2013 to increase and strengthen trade, infrastructure, and cooperation. The initiative has two main arms: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the New Maritime Silk Road, both of which will connect China with the rest of Asia, North Africa, and Europe. BRI projects will provide much-needed infrastructure creation or repairs, increased trade efficiency, economic growth, and improved regional cooperation.

While many are touting the initiative’s benefits, many are also questioning the real reasons behind it. Many BRI recipients are underdeveloped or undeveloped nations and are unlikely to be able to repay the loans granted by Chinese entities. Some recipients use their new BRI-created infrastructure as loan collateral, and when they default, the lending organization is given a lease for the asset. The lease gives the lenders control of a nation’s important infrastructure. Also, the BRI could be used by China to increase its regional influence and boost market share and profitability for its state-owned enterprises.

Possible benefits of the BRI for China include reliable shipping routes for their goods, bigger market share, and increased economic growth in regions that didn’t benefit from the recent economic boom. Some challenges include exorbitant costs, backlash when countries become indebted to Chinese entities for the loans, and security for construction crews as some regions who are negotiating infrastructure deals have security challenges including terrorism.

Canada could benefit from the BRI with an increase in exports as they have a longstanding relationship with China as well as favoured standing with many Asian nations through existing trade agreements. Possible challenges include being located so far from the region, which could deter companies working on the projects from sourcing materials from Canada. Also, the current tensions between Beijing and Ottawa could prevent Canadian companies from providing goods or services. And the current tensions between Beijing and Washington could also complicate matters as their relationship is vital to how Canada progresses with China.

What is BRI?

China created the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 with aims to improve cooperation and connectivity on a trans-continental scale (The World Bank, 2018). It is designed to strengthen trade, investment, and infrastructure links between China (the creator of the initiative) and the countries along either the land or maritime trade routes (The World Bank, 2018). By October 2018, the number of countries involved in the BRI had ballooned to 117 (Joy-Perez & Scissors, 2018). Collectively the members account for 62% of the world’s population, 75% of known energy reserves, and more than 30% of the world’s trade and Gross Domestic Product (The World Bank, 2018). There are two main components of the BRI: the Silk Road Economic Belt, and the New Maritime Silk Road (The World Bank, 2018). The Silk Road Economic Belt will connect China with Central and South Asia and ultimately Europe whereas the New Maritime Silk Road will connect China with countries in South East Asia, the Gulf, North Africa, and finally Europe (The World Bank, 2018). The initiative’s full scope hasn’t been determined yet; however, the Belt and Road Initiative was recently understood to be available to all nations as well as regional and international organizations (The World Bank, 2018).

The BRI will help to increase economic efficiency in participating regions because as transportation infrastructure is improved, transportation times and costs will decrease, thereby increasing trade and flow of goods (The World Bank, 2018). Also, local employment in the areas where projects are built will rise as workers are employed to build the infrastructure or hired to work at and maintain the infrastructure once completed. Increased economic efficiency and local employment will boost the economies and standards of living for these areas of the recipient country.

For perspective on the potential economic benefits of the initiative, the Africa-Europe-Asia region had annual trade of more than USD 2 trillion according to World Bank and European Union data, compared with USD 1.1 trillion in trans-Atlantic trade (Khanna, 2019).

However, an academic article in the Canadian Security Intelligence Service publication Rethinking Security: China and the Age of Strategic Rivalry state that when you ignore the propaganda campaign, you see that the Chinese government has two real objectives with the Belt and Road Initiative (Government of Canada, 2018). Firstly they want to increase their economic authority by finding new markets for their state-owned enterprises where they can increase sales, sell some of their excess industrial capacity, and increase their international market share (Government of Canada, 2018). Secondly, the initiative will help to reduce the risk of political instability and social unrest within China and also boost the country’s energy security (Government of Canada, 2018). China wishes to leverage its recent economic success with undeveloped markets to control vital infrastructure assets and gain support from other nations for Chinese interests (Government of Canada, 2018).

Is There a Common Ground Between China and Canada on BRI Platform?

A. How Might China Benefit from BRI? (How Value Can Be Added to the Chinese Stakeholders?)

The Belt and Road Initiative will benefit Chinese stakeholders because there will be an increase in reliable shipping infrastructure (highways, ports, and railways) to help move their products. Also, as the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the nations along the BRI routes increases with the improved infrastructure and economic activity, their citizens will have more money to spend on goods from China – either for personal or commercial use.

Also, in recent years, the eastern region of China has experienced rapid economic growth. However, the western and southern regions of the country were left behind and didn’t benefit in the same manner or to the same extent (Brown, 2019). With the increase in the number of BRI projects, the have-not regions of China could benefit from development, economic prosperity, and increased integration and competitiveness (Brown, 2019).

Furthermore, it is the concerned view of the Indian government that China is using the Indian Ocean region as a new market for it’s high-end manufactured goods and as a source of natural resources (Khurana, 2019). Both points were voiced as concerns by the Indian government, but they will also be a benefit for Chinese stakeholders. The stakeholders will now have access to additional natural resources that they may not be able to source elsewhere and increased revenue from sales of its high-end manufactured goods.

B. How Might Canada Benefit from BRI? (How Value Can Be Added to the Canadian Stakeholders?)

Canada has a long-standing relationship with China and is represented in China by an embassy, several consulate generals, and a network of ten trade offices throughout the nation (Government of Canada, 2019a). In 2018 Canada exported CAD 27.6 billion to China and imported CAD 75.6 billion from China (Government of Canada, 2019b). The Canadian Trade Commissioner Service identified several sectors in China which could provide Canadian companies with the best opportunities for trade, including infrastructure, building products, and related services, transportation, information and communication technologies, and automotive (Trade Commissioner Service, 2018). These sectors could be involved in BRI projects, as well (Trade Commissioner Service, 2018).

In 2018 Canada joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a multilateral development bank that concentrates on economic development through infrastructure financing in Asia (Department of Finance Canada, 2018). The bank currently has 97 members, including Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, and India (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, 2019). Canada’s participation in the AIIB will help to foster stronger relations with countries in the Asia-Pacific region and also provide commercial opportunities for Canadian companies to work on infrastructure projects financed through the bank (Department of Finance Canada, 2018). It was reported in March 2019 that a Canadian consulting firm had won a procurement contract through the AIIB with other Canadian companies bidding on additional contracts (Smith, 2019).

Canadian companies could gain access to BRI projects through Canada’s existing trade agreements. In 2018, Canada ratified the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) which is a free trade agreement between Canada and ten nations in the Asia-Pacific region, including Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, and Brunei (Government of Canada, 2019c). Due to its participation in the TPP Canada now enjoys privileged access to key markets in both the Asian and Latin American regions (Khanna, 2019).

Canadian firms could also gain access to markets that they don’t currently have a trade agreement with but are participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. They can do this by partnering with Chinese companies in the engineering, procurement, and construction sectors who will supply or construct the infrastructure projects along the maritime and silk road trade routes (Liew, 2018).

What are the Possible Challenges?

A. For China?

There are several possible challenges for China with the Belt and Road Initiative. Firstly, costs can be prohibitively expensive. Much of Asia and Africa where the BRI will transverse is undeveloped or underdeveloped. Therefore, existing infrastructure may be very rudimentary if it exists at all. The possible economic payoff may not be worthwhile for the expenditures required.

Also, there recently has been a backlash against overt Chinese involvement in countries (Marlow & Li, 2018). For instance, after the previous federal government was voted out in the Maldives, authorities discovered that a large amount of debt had been borrowed from Beijing to build a new bridge, airport runway, housing developments, and a hospital (Marlow & Li, 2018). They also found out that the previous authorities had rejected a bid of USD 54 million for the new hospital in favour of an inflated USD 140 million bid from the Chinese (Marlow & Li, 2018). Today, the Maldives owes China USD 1.5 billion in construction costs for reclamation projects (or approximately 30% of it’s GDP) (Khurana, 2019). Several nations, including Australia and Japan, have also begun to intensely scrutinize Chinese investments in their critical infrastructure such as network systems and key ports (Marlow & Li, 2018).

Also, many of the nations that have agreed to BRI projects are now heavily in debt to China with no ability to repay the loans (Brown, 2019). Due to this, there have been allegations that the Chinese government is practicing “Debtbook Diplomacy”; by becoming a creditor nation, they can use their influence to advance their geopolitical objectives (Brown, 2019). Additionally, many developing nations use their new BRI funded assets as collateral on the BRI loan that was used to pay for the project, essentially giving the lenders leases of the assets in case of a loan default (Brown, 2019). For example, in 2017 the federal government of Sri Lanka sold a 70% ownership lease of a newly constructed port to the state-owned China Merchants Group for USD 1.1 billion for a term of 99 years (Brown, 2019). The Chinese government has rejected allegations that it’s BRI initiative and investment decisions and subsequent lending are designed to drown recipients in debt they cannot repay and therefore give Beijing political clout in the nation (Brown, 2019). However, some potential BRI recipients are now scrutinizing and canceling Chinese lending, including in Malaysia and Uganda (Brown, 2019).

Correspondingly the US has created an agency in response to the Belt and Road Initiative to lend up to USD 60 billion for infrastructure construction and improvements as an alternative lending scheme (Brown, 2019). The International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC) will seek to employ local workers and avoid the debt trap problems seen with the BRI (Brown, 2019). However, as competition increases between the BRI and the IDFC, the tensions between Washington and Beijing could increase (Brown, 2019).

Lastly, some of the nations who have negotiated infrastructure deals with China have security challenges within their borders, including terrorism. For instance, China and Pakistan have formalised agreements on Chinese investments totaling USD 46 billion over the next 10-15 years (Markey & West, 2016). However, a primary obstacle to the full implementations is security, especially in Pakistan where the Pakistani Taliban, East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), Islamist militants and other anti-state militant groups could attack construction crews and disrupt the trade of goods (Markey & West, 2016). Islamist militant groups have already kidnapped construction workers in Pakistan and hinted at intensifying their terrorism to include more Chinese targets (Markey & West, 2016).

B. For Canada?

There are three possible challenges for Canada. Firstly, being located so far away from both the Silk Road Economic Belt and the New Maritime Silk Road means that a shipment of Canadian raw resources or finished products could be cost prohibitive for projects with inexpensive alternatives possibly available closer to the region.

Secondly, existing or soon to be ratified trade agreements that limit or prohibit trade with other nations could be challenging for Canada. For example, the newly negotiated version (but still to be ratified) of the North America Free Trade Agreement (often referred to as USMCA) could prevent Canada from engaging in free trade talks with China. Clause 32 states that the signatories are required to tell one another if they initiate free trade talks with a non-market economy, a term believed to reference China (Vomiero, 2019). If one of the signatories starts free trade talks with a non-market economy, the other signatories have the right to withdraw from the agreement (Vomiero, 2019).

Thirdly, Canada-China relations have been on a downward trend recently. In December 2019 Canadian authorities arrested the Chief Financial Officer of Huawei, a major Chinese technology company, who had been charged by the United States with fraud connected to alleged violations of the Iran sanctions (Lee, 2019). Since then China has detained several Canadians and stopped shipments of Canadian canola destined for their country, with concerns by the Canadian Finance Minister Bill Morneau that they could do the same to other Canadian products (Lee, 2019). Minister Morneau also stated that the current tension between China and the United States, a close Canadian ally, is complicating the situation, as their relationship is integral to how Canada can move forward with China (Lee, 2019).

Bibliography

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. (2019, April 24). Members and Prospective Members of the Bank. Retrieved from Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/governance/members-of-bank/index.html

Brown, E. (2019, February 4). The Belt and Road Initiative: Investment Opportunities in China’s “Project of the Century”. Retrieved from Global Risk Institute: https://globalriskinstitute.org/publications/the-belt-and-road-initiative/

Department of Finance Canada. (2018, December 18). The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Retrieved from Department of Finance Canada: Infrastructure

Government of Canada. (2018, May 8). Expanding regional ambitions: The Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from Government of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/security-intelligence-service/corporate/publications/china-and-the-age-of-strategic-rivalry/expanding-regional-ambitions-the-belt-and-road-initiative.html

Government of Canada. (2019a, March 22). Canada-China Relations. Retrieved from Government of Canada: https://www.canadainternational.gc.ca/china-chine/bilateral_relations_bilaterales/index.aspx?lang=eng

Government of Canada. (2019b, April). Factsheet. Retrieved from Government of Canada: https://www.canadainternational.gc.ca/china-chine/bilateral_relations_bilaterales/China-FS-Chine-FD.aspx?lang=eng

Government of Canada. (2019c, February 26). Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Retrieved from Government of Canada: https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/cptpp-ptpgp/index.aspx?lang=eng

Joy-Perez, C., & Scissors, D. (2018, November 14). Be Wary of Spending on the Belt and Road. Retrieved from American Enterprise Institute: http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Updated-BRI-Report.pdf

Khanna, P. (2019, April 30). Washington Is Dismissing China’s Belt and Road. That’s a Huge Strategic Mistake. Retrieved from Politico: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/04/30/washington-is-dismissing-chinas-belt-and-road-thats-a-huge-strategic-mistake-226759

Khurana, G. S. (2019, April). India as a Challenge to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Asia Policy, 14(2), 27-33. doi:10.1353/asp.2019.0027

Lee, Y. N. (2019, June 8). ‘We’re at an impasse’ with China, says Canadian Finance Minister Morneau. Retrieved from CNBC: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/06/08/canada-china-relations-at-impasse-says-finance-minister-bill-morneau.html

Liew, C. W. (2018, April 20). Top 5 sector opportunities for Canadian businesses in China. Retrieved from Export Development Canada: https://www.edc.ca/en/blog/opportunities-for-canadian-businesses-in-china.html

Markey, D. S., & West, J. (2016, May 12). Behind China’s Gambit in Pakistan. Retrieved from Council on Foreign Relations: https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/behind-chinas-gambit-pakistan

Marlow, I., & Li, D. (2018, December 10). How Asia Fell Out of Love With China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from BNN Bloomberg: https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/how-asia-fell-out-of-love-with-china-s-belt-and-road-initiative-1.1181199

Smith, M.-D. (2019, March 25). Canadian companies start to benefit from membership in China-based infrastructure bank. Retrieved from National Post: https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/canadian-companies-start-to-benefit-from-membership-in-china-based-infrastructure-bank

The World Bank. (2018, March 29). Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from The World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative

Trade Commissioner Service. (2018, November 5). Doing business in China. Retrieved from Trade Commissioner Service: https://www.tradecommissioner.gc.ca/trade_commissioners-delegues_commerciaux/country-pays/china-chine.aspx?lang=eng

Vomiero, J. (2019, March 30). Is Canada ready for free trade with China? Some experts say it’s a ‘non-starter’ right now. Retrieved from Global News: https://globalnews.ca/news/5113811/canada-china-free-trade-non-starter/